Here's the English translation: ---

Here's the English translation: ---What can a porcelain horseman tell us?

Have you ever paused to look at a porcelain figurine displayed behind the glass of a museum showcase?

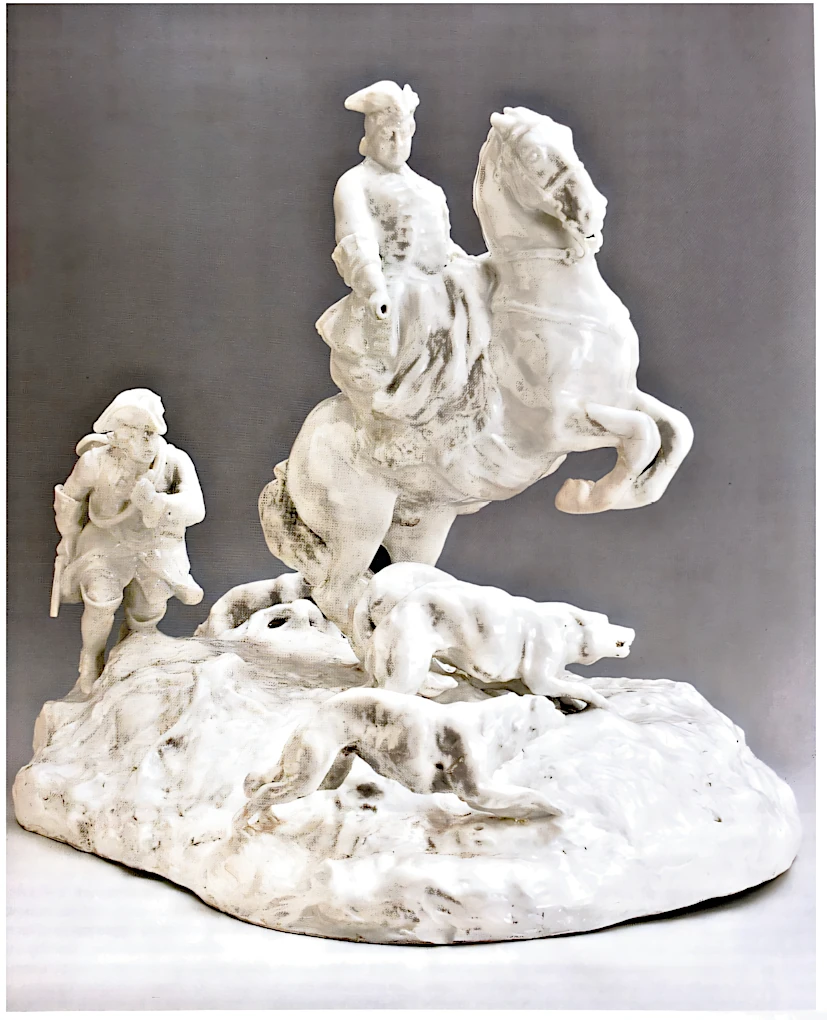

Not just a pretty trinket, but a true sculpture—with fragile dynamism, with history in the horse’s gaze, with the tiniest details of a uniform that reflect an entire era. As if someone, knowing that times would change, decided to preserve their breath in fired white clay.

Few people know that behind the scenes of the Imperial Porcelain Factory, famed worldwide for its opulence and precision, not only creative experiments played out, but genuine dramas of psychology, statehood, and art as well. After this story, you'll never look at a porcelain miniature the same way again. You'll see not just a "collectible exhibit," but a key to a dialogue between past and future, between the artist’s dream and the ideology of the Empire.

First Act — A Pearl on the Front Line: Baron Rausch von Traubenberg and the Game of Small Sculpture

Paris, 1907. A mysterious young man, tall, always polite, with thin military mustache, exhibits his works for the first time at the Autumn Salon. This is Karl Karlovich Rausch von Traubenberg, a hereditary military man, a porcelain rebel, a dreamer, a student of Ashbe and I. Grabar. He grows up in Bavaria, learns to sculpt to music in Hildebrand’s studio. Behind him lies all of Europe—with its bronzes, marbles, showcases in cigarette smoke, its great cities and their endless search for an artistic voice of their own.

It is only 1908, and St. Petersburg draws the baron into its cold northern whirlwind.

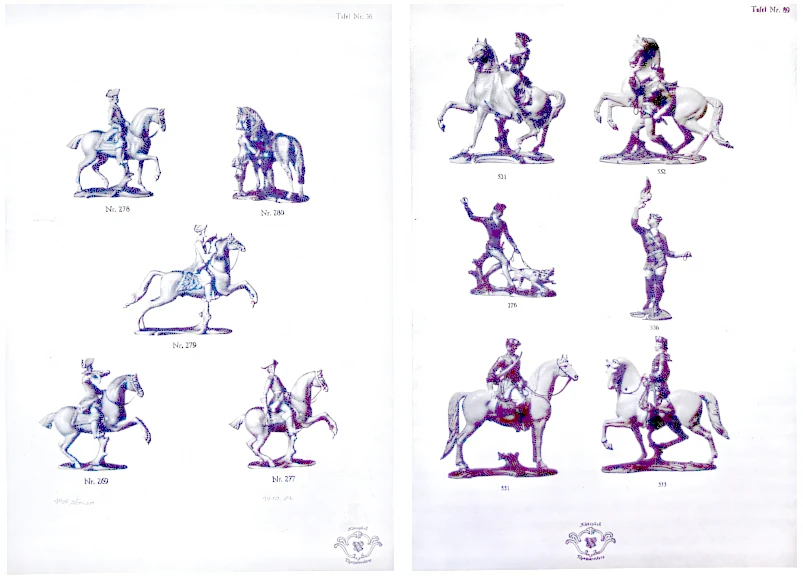

Sheet No. 89 from the 1912 sales catalog of the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory.

Here, at the Imperial Porcelain Factory, doors open—and so do the pressure gauges. The factory is a world with two faces: one is the academic muse of national traditionalism; the other is a neighbor, green with envy, watching as young artists try to breathe "new life" into porcelain. It is precisely Rausch von Traubenberg who brings the European wind here, but from the very beginning, his journey is far from a quiet procession up a marble staircase.

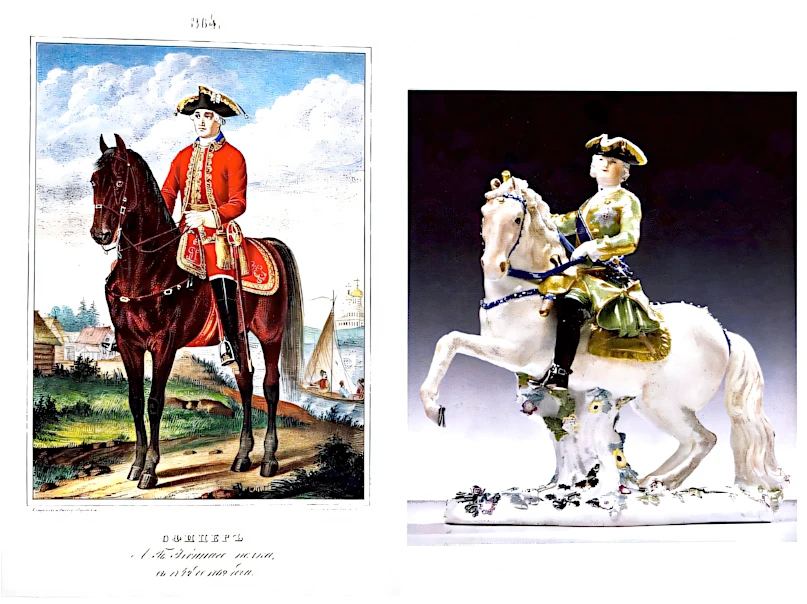

"Empress Elizaveta Petrovna on horseback". Model by J. J. Kaendler. 1743. Meissen Porcelain Manufactory. Unmarked. Height—23.5 cm. Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Porzellansammlung.

The porcelain manufactory is a strict, official lady. Its assortment reflects the will of the imperial court; every work is strictly regulated, and a bureaucratic order written with a quill cuts off everything bold and too lively. Yet, gradually, new faces, ideas, and trends start to appear in this royal utopia. This was written about bluntly by Nicholas Roerich, who lamented in his notes: among the talented craftsmen, there are no true poets of porcelain—those capable of turning a lump of clay into a reflection of the present...

Officers of the Life Guards Horse Regiment, 1796–1801, 4th and 5th squadrons

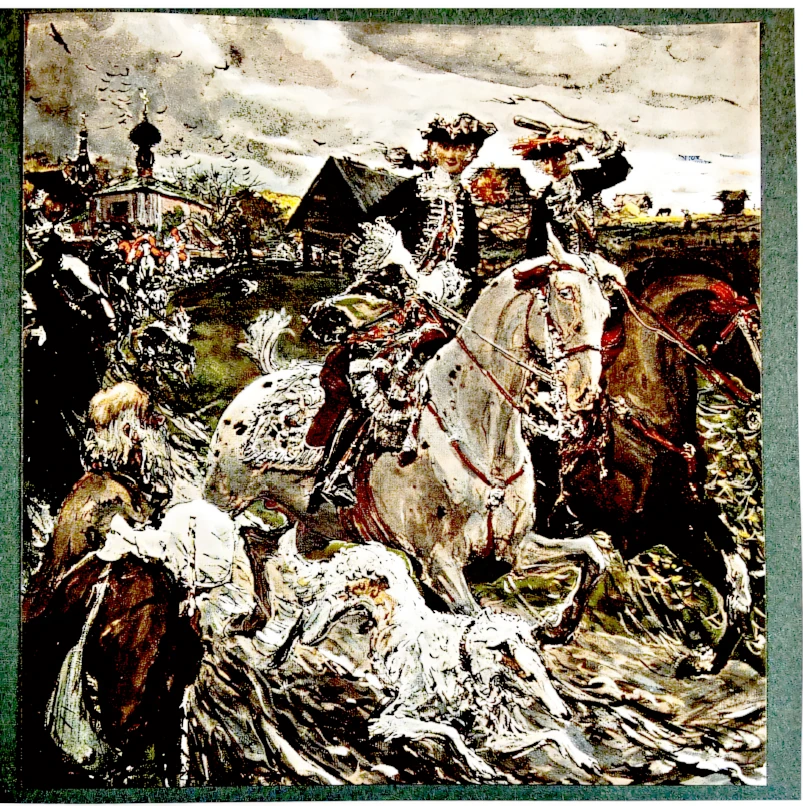

Just think: the Imperial Porcelain Factory was not just an industrial behemoth—it created symbols: from national heroism to the banal napkins for empresses. And one of the first to be able to reshape this system,Here is your text translated into English: Raush von Traubenberg was appointed. For the factory, which craved propagandistic power and new artistic blood, the baron was the perfect compromise. On the one hand, status, lineage, and military spirit; on the other — a young European perspective, unrefined boldness in his approach to composition and style. However, any innovation takes root with difficulty in an environment where every brushstroke must receive the highest approval, and every shade of porcelain white must pass no less a rigorous scrutiny than a new regiment under Peter III. Sculpture: "Officer of the Life Guard Cannon Regiment during the reign of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna" Separate impression by Apollo, 1913 Sculpture: "Officer of the Life Guard Cannon Regiment during the reign of Emperor Paul I" Separate impression by Apollo, 1913, St. Petersburg. Act Two — Riders on Something Greater: "The History of the Russian Guard" as a Mirror of the Country Before you is not just a rosy-cheeked officer on an expensive horse. This is an ideological concept: the figure of a serviceman embodying the scale and magnificence of the Empire. In the early 20th century, the Imperial Porcelain Factory, once the favorite plaything of the court, found itself at the epicenter of an ethical storm: on one side, the grand series "Peoples of Russia" (almost a miniature theater of national characters), on the other — dramatic battle scenes where eras come to life as if caught on film. Sculpture: "Officer of the Guards Cuirassiers during the reign of Emperor Alexander I (1802—1809)". 1910 Molded by P.V. Shmakov (1866—?). Green mark: "N II" under a crown and date "1910". Sculpture: "Horse Guardsman, time of Emperor Alexander I" And here appears Raush von Traubenberg with his "History of the Russian Guard." The Guard — elite, on display, a system of values...Here is your translation into English: The artist works on creating an entire series of miniatures with almost maniacal fervor: he corresponds with military historians, pores over multi-volume works on uniforms, corrects sketches in antique albums, and studies the breed of each horse so that it is not just a “support,” but an independent character, an actor in a personal tragedy. Every fold of the uniform is important here, glowing in the matte blue of the porcelain; every movement seems like a captured nerve from a bygone century. Sculpture: "Officer of the Life Guards Hussar Regiment in the Reign of Emperor Alexander I" (1812–1820) The distinctive feature of these sculptures is the almost physical tangibility of the era through the material itself. If you listen closely, the porcelain officer from the time of Elizabeth Petrovna has a crystal-clear clink of armor that draws in the very spirit of the 18th century, while the Andalusian horse is recreated with nearly anatomical precision. The baron draws inspiration from Munich manufactory catalogs, albums on the history of military costume, and even personal family legends (his uncle translated the “History of the Cavalry” into Russian). His work is not just illustration, but a nuanced story of psychology: how society, the army, and even the image of the hero have changed. Sculpture: "Officer of the Life Guards Hussar Regiment at the Beginning of the Reign of Emperor Alexander I" (1801) A parallel with the present: today brands, pop culture heroes, and even bloggers copy the images of the elite, building entire businesses around the "symbolism of success." Back then, this code was encoded in porcelain figurines; the entire elite of St. Petersburg wanted their own symbol, their own miniature of acquired eternity. Doesn't this seem similar to how we collect "stories" and push notifications today?Here's the English translation of your text: 683-bd33-4690-81fe-751c5f349014.webp">

Act Three — For Whom Does the Porcelain Toll? Hooves That Resound Through Time

Porcelain is a material you can't help but feel, touch, fall in love with completely. There is no room for half-measures here: Rausch describes the Andalusian horse with the obsession of the best 19th-century animal artist, meticulously ensuring that each rider is given not just "props," but an individual equestrian portrait. The boundary between art and science disappears. Would you believe that, in the baron's workshop, they seriously argued over the shape of a hussar horse's ears, or that each officer is depicted on a strictly defined breed — because the Imperial Army would not have allowed a "foreign" coloring?

Critics later called the porcelain sculpture "alive"—as opposed to painted mannequins, bright but cold. There is movement in these figurines, a nerve, a touch of individual destiny... This is not just "minor art," declares the era, because the line between a "home figurine" and a cultural code is gone. They were created as ideological companions, but outlived their era and did not become faceless artifacts. "One can only rejoice at the appearance of an artist so actively contributing to the revival in our country of the delightful branch of artistic production—artistic porcelain," wrote the art historian Rostislavov.

Sculpture "Italian Greyhound", Late 1820s–1830s, Factory and sculptures by Baron Rausch von Traubenberg // Biscuit porcelain, gilding, chasing; base — smalt. State Hermitage Museum

Where the Past Becomes Present: What Forgotten Masterpieces Call For

Collaboration with the Imperial Porcelain Factory became for Rausch von Traubenberg not only a period of glory, but also an eternal experiment: porcelain became a laboratory of hybrid meanings, where small things have long vied with great ones, and history becomes your own personal toy — a key to the doors of the past.

Today, when miniatures from the past are easily dismissed as “secondary,” it’s worth remembering: it is precisely these “small” things that reflect the larger story. The monumentality sought in Rausch’s porcelain was never a “monument,” but always — a dialogue with those who look and can make themselves peer into the details.

And if next time you happen to come across a stern army of “guardsmen” behind museum glass, or an ensemble of “the tsar’s hunt,” pause for a moment.

Think: Don’t your own day, your daily rituals, connections, and passions — these little and fragile things — turn into a grand story about time?

What if every porcelain figurine holds a real drama — just waiting for someone to be able to tell it?

...

And what work of art has ever made you stop and reflect?