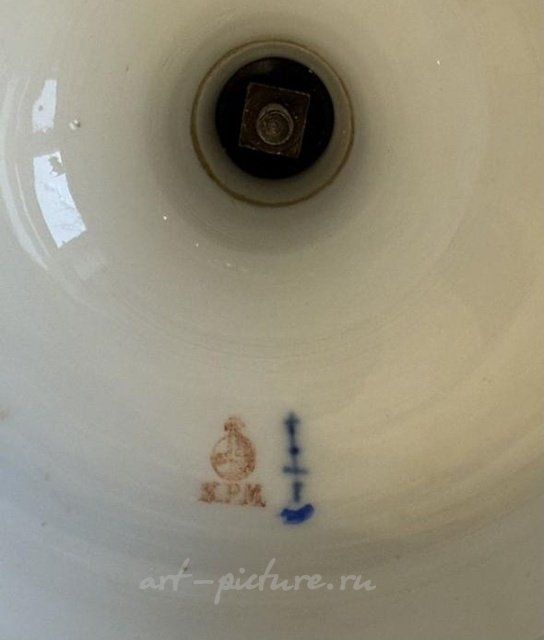

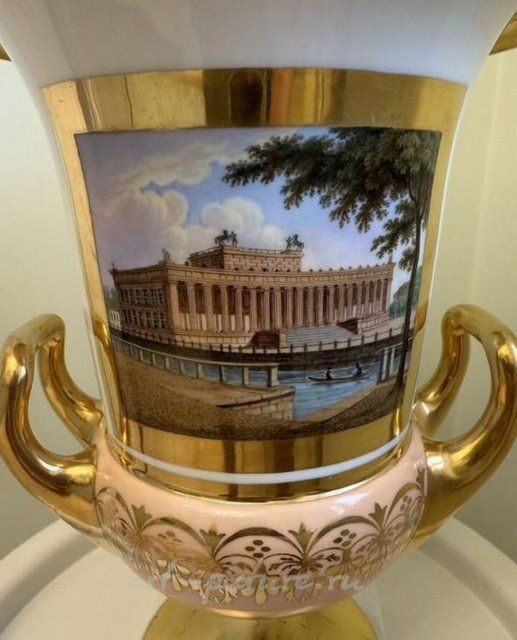

Ваза декоративная, антикизированной формы (в виде кратера), украшена с двух сторон белого тулова миниатюрной живописью в жанре «ведута» (архитектурные пейзажи). Отогнутый наружу венчик, ручки и круглая ножка - позолочены. Нижняя сферическая часть корпуса окрашена в нежный розовато-желтый цвет и декорирована росписью золотом в виде стилизованной гирлянды из пальметт. Фарфор, полихромная миниатюрная живопись (роспись), позолота, цветное крытье, роспись золотом. Размеры: общая высота - 31 см. Клейма: на внутренней части подставки ножки фирменная марка производителя подглазурного изображения синей кобальтовой краской скипетра и надглазурнь красный штамп в виде «державы» с аббревиатурой «КРМ». Германия, Королевская Фарфоровая Мануфактура в Берлине. Представленная декоративная ваза с архитектурными пейзажами на тулове относится к вещам ярко выраженного интерьерного характера, которые традиционно рассматривались как произведения декоративно-прикладного искусства, призванные подчеркнуть респектабельность домашней обстановки. Данная ваза отличается высоким уровнем художественно-технического исполнения, прекрасной сохранностью и высококачественной позолотой миниатюрной росписью. На основе визуального анализа и имеющегося клейма декоративная ваза может быть и отнесена к продукции знаменитой Берлинской Королевской Мануфактуры. Изделие изготовлено в неоклассических традициях художественного ассортимента мануфактуры втор. четв. 19 века (1830-1850 гт.), когда его основной стилистической чертой хотя и остается обращение к формам античного искусства, преобладание четких контуров, стремление к гармонии пропорций, но при этом роспись многих предметов уже несет на себе отпечаток нового стиля эпохи Историзма - бидермейера. Особенно востребованной продукцией Берлинской Королевской Мануфактуры этого времени являются декоративные вазы с миниатюрной росписью в виде архитектурных пейзажей (ведута - виды городов, отдельных зданий и городских памятников) Берлина, запечатлевшие наиболее знаменитые архитектурно-исторические памятники и городские монументы. Поверхность вазы в соответствии с европейскими традициями декорирования фарфоровых изделий рассматривалась как холст, на которую наносилась миниатюристом уменьшенная или несколько видоизмененная копия живописного произведения или гравюры. В нач. 20 века мануфактура по-прежнему выпускала изделия в стилистике классицизма и ампира (немецкий неоклассицизм кон. 19-нач. 20 в.) и общественный интерес к такому виду художественной продукции широко известной и к тому же старейшей мануфактуры в Европе, по-прежнему, был очень высоким. Данная декоративная ваза наглядно подтверждает этот факт. Так, на одной стороне тулова рассматриваемого изделия в золотом картуше-раме изображено здание Старого музея в Берлине, выполненное с некоторыми изменениями по гравюре «Старый музей» немецкого художника Ф.А. Тиле 1830 г. На другой стороне вазы - вид с городской набережной на бронзовый памятник курфюрсту Фридриху Вильгельму Берлине, являвшийся одной из самых известных достопримечательностей немецкой столицы. Обильная позолота на венчике, ручках и ноже, орнаментальная роспись золотом в нижней части вазы в совокупности с искусно выполненными архитектурно-пейзажными миниатюрами придают предмету дорогой и изысканный вид. Такие изделия великолепно украшали интерьер рабочего кабинета или гостиной в частном доме, располагались на каминной полке дорогой буржуазной квартиры, радуя глаз эстетическим совершенством предмета искусства. Не потеряли своего значения декоративные вазы немецкого производства и в наши дни, оставаясь коллекционным фарфором высокого качества и ручной работы. Данная ваза имеет антикварное, историко-художественное и культурное значение. Обзор рынка фарфора KPM Оценка рынка фарфора — довольно непростая задача. На ценообразование влияют множество факторов: ; время создания вещи, ее уникальность и редкость, качество живописи и, наконец, ее состояние. Как известно, для анализа рынка предметов многие коллекционеры опираются на каталоги торгов западных аукционов. Но оценка вещей аукционом не является абсолютным индикатором цен, поскольку аукцион - третья сторона. Большинство вещей продают и покупают, как правило, дилеры, которые более чем готовы вкладывать деньги в хорошие вещи. Зачастую вещи, купленные дилером, будут перепроданы коллекционерам по гораздо более высокой цене, такой, которую вы не найдете ни в одном каталоге! В последние годы в России заметно возрос интерес к предметам искусства. В любой стране, переживающей бурный экономический подъем, появляются весьма обеспеченные люди, которые, заработав деньги и удовлетворив все свои первичные потребности, обращают свой взор на предметы искусства. Сначала в ряды крупных покупателей антиквариата влились арабы, японцы, за ними — индусы, не заставили себя ждать и россияне. Сейчас Европа на очередной модной волне — китайской. «Новые» китайцы скупают буквально все, что может, по их мнению, вписаться в интерьеры их мини Версалей! За короткий период произошло «вымывание» с антикварного рынка колоссального числа предметов. Немаловажную роль в этом сыграли и многочисленные туристы, которые, путешествуя по странам Европы, приобретали на память чашку или тарелку с прекрасным видом, благо цены на фарфор 10-—15 лет назад были совсем другого порядка. Сейчас же даже в Вене не купить видовых чашек — не то что Венской мануфактуры, но даже «типа Вены» не осталось! Та же ситуация во Франции и в Германии, не говоря уж о России. Если в 90-е годы XX века на российском антикварном рынке предложение в разы превышало спрос, то сейчас ситуация изменилась кардинально. Пополнить коллекцию хорошим предметом — большая и очень дорогостоящая удача. С одной стороны, учитывая объемы производства, фарфор KPM — нередкий гость на антикварном рынке. С другой — редкие и уникальные вещи с высококачественной живописью встречаются нечасто и ценятся весьма высоко. Еще несколько лет назад цена на ординарные чашки составляла 300—500 евро. Сейчас на европейском рынке стоимость ординарной чашки колеблется от 1000 до 3000 евро. Цена же высокохудожественной чашки со сложной архитектоникой (с маскаронами, лепными элементами и т.д.) и превосходной живописью может варьироваться от 5000 до 15 000 евро. Нельзя не упомянуть о чашках, посвященных Тильзитскому миру 1807 года и декорированных портретами Александра I и Наполеона, а также о серии чашек, посвященных битвам при Лейпциге и Ватерлоо и декорированных портретами монархов тех стран, чьи войска принимали в них участие. До захвата Пруссии Наполеоном I также была выпущена небольшая серия парных чашек с портретами Александра I и его супруги Елизаветы Алексеевны. Эти предметы— несомненно, раритетные, и цена на них может начинаться от 25 000 евро. Для справки могу сказать, что за последние 15 лет чашки упомянутых серий на европейских аукционах не встречались. Цена на берлинские ординарные тарелки сегодня колеблется от 1000 до 2000 евро за экземпляр. Стоимость топографической тарелки может составить от 3000 до 15000 евро. Тарелки с сюжетной живописью (1790—1840 годов) могут быть оценены от 10 000 евро. А модные и популярные нынче «военные» тарелки уходят с европейских аукционов по цене от 10000 до 40 000 евро, в зависимости от их состояния и времени создания. Цена на вазы высотой около 30 см — 5000 — 10000 евро, высотой около 50 см — от 20 000 до 50 000 евро. Вазы выше 70 см могут стоить от 50000 до 150000 евро. Так, на весеннем аукционе в Берлине ваза высотой 70 см была продана за 130 000 евро. Естественно, что цены на фарфор КРМ со временем будут увеличиваться. Как и в любом бизнесе, они на антикварном рынке зависят от спроса и предложения, а поскольку спрос на фарфор устойчиво растет (это касается не только берлинского, но фарфора вообще), со временем будет все меньше предметов для удовлетворения этого спроса. Я отнюдь не призываю всех инвестировать в искусство, есть много других сфер для вложений капиталов с более быстрым и предсказуемым получением прибыли. На антикварном рынке возможна и спекуляция. Но самый лучший инвестор — серьезный коллекционер. Чтобы вкладывать деньги в фарфор, надо обладать глубокими знаниями, иметь хорошего консультанта и долгосрочные планы. Однако и это не всегда гарантирует быстрый успех, поскольку ситуация на рынке может зависеть от субъективных факторов, таких, как мода, например. Чтобы объективно оценить прибыль, должно пройти, по меньшей мере, 5—10 лет. И вполне вероятно, что тарелка KPM, купленная в 2022 году за 5000 у.е., через 10 лет вырастет в цене вдвое, а то и втрое.

CountryGerman Empire 1871 - 1919

Lot location Moscow ( 77 )

A comment

Payment by agreement

Please check the payment methods with the seller when making a purchase

Delivery by agreement

Check the delivery methods with the seller when making a purchase

Approximate prices in Russia

Royal Porcelain Manufacture of KRM

Additional lots

Royal Porcelain Manufacture of KRM

Description

Additional articles

Ваза декоративная в виде кратера, в жанре «ведута» (архитектурные пейзажи) KPM

KPM Porcelain: Guide to Berlin’s Royal Porcelain Factory

KPM Porcelain: Guide to Berlin’s Royal Porcelain Factory

Viewed lots

The lots you have recently viewed